Our Blog

It is a blinding bright winter morning in Johannesburg and I am sipping on honeybush rooibos tea while I wait for one of my artist heroes: Mr. William Kentridge. We are meeting again for the first time since the opening of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York to discuss his dream of being an elephant, how apartheid influenced his practice, what keeps him curious, and the exercise of embracing a multiplicity of mediums. This was my third time in South Africa, where I have been travelling annually to support an arts empowerment program at Nkosi’s Haven (an orphanage founded with the aim of looking after mothers and children directly affected by HIV/AIDS).

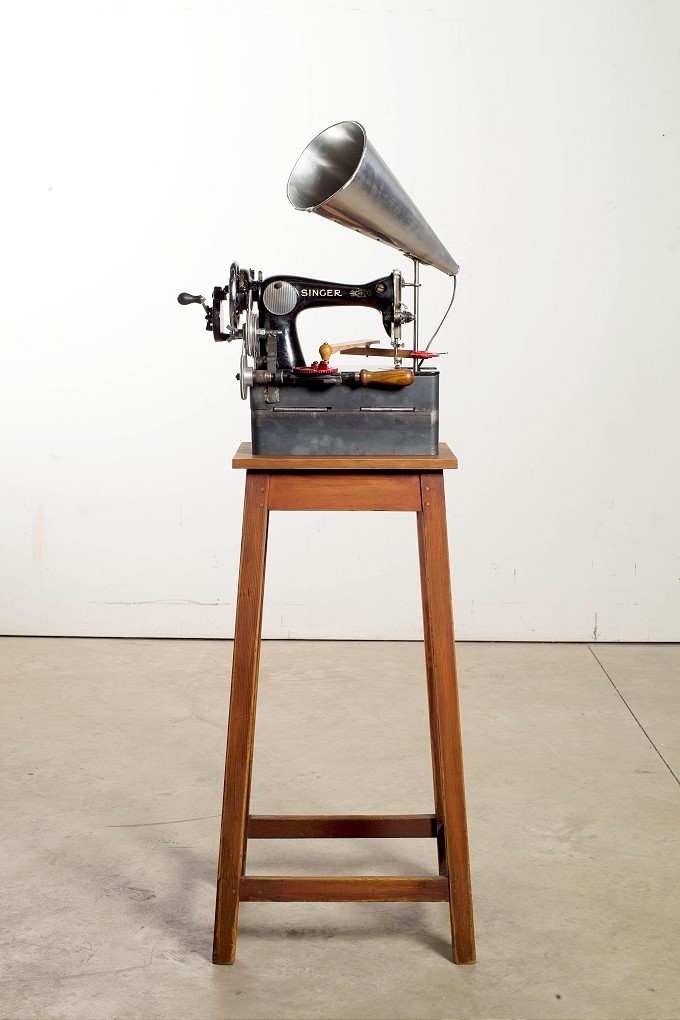

A lone sofa sits in a wide open space with a simple Maplewood coffee table in front of it. The proportions of the space lead me to think that it could be a double decker bus garage designed by Mies van der Rohe. Instead of tall buses, exquisite three-dimensional corpses occupy the place: musical machines that feel like oversized puppets. My memory keeps going back to one, a rolling tri-pod upholding a sewing machine with megaphones for arms. These would soon thereafter be shipped to New York for his solo show at the Marian Goodman Gallery titled Second-hand Reading.

It is inspiring to be a witness to this man’s experimentation. William Kentridge (born 28 April 1955) is a South African-artist best known for his prints, drawings, and animated films. These are constructed by filming a drawing, making erasures and changes, and filming it again. He continues this process meticulously, giving each change to the drawing a quarter of a second to two seconds’ screen time. What I find so stimulating about his work is that it often defies categorization. The man dabbles from gestural two-dimensional illustrations to films to operas.

Kentridge’s artworks are among the most sought-after and expensive works in South Africa: a major charcoal drawing by Kentridge can cost as much as $250,000 USD. During Sotheby’s 2011 spring auction in New York, one of Kentridge’s pieces (a procession of 25 small bronze sculptures) set an auction record of $1.5 million (£1 million). Below is an edited version of our conversation.

YA: Let’s go back to when you were a child, say 5 to 10 years old, what did you imagine yourself doing as a grown up? What did you want to be?

WK: Family history has it that when I was three and I was asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said ‘elephant’ and I suppose this is the closest it’s going to get.

To being an elephant.

I suppose for years I thought I would be an architect or an engineer. I never really thought I would be lawyer, because both of my parents are. For some years, I thought I ought to have been a lawyer, even though I wasn’t going to be one. And I was reduced to being an artist. All the other things I tried failed. So I tried being an actor, went to theater school and failed as an actor and so on…until art.

YA: What would you define as your favorite occupation?

WK: Being on active duty in the studio. That’s my favorite occupation.

YA: What do you consider your life’s greatest achievement up to now?

WK: I suppose, seriously, it’s being able to understand that the undertaking to work in many different fields is not – did not weaken any one of them. I was strengthened by the multiplicity of different fields.

So I think that was a battle, in a sense, to convince myself of that. That I wanted to be just painting, or just filming, or just acting, but doing all of them.

YA: I recently spoke to Anish Kapoor about the idea of keeping his sculptures visually impactful and also meaningful. I don’t know if there’s a shock value or an aesthetic power to the way that something looks and appears at first to an audience, and then, that weighed against its meaning. Can you speak to the challenge of making something that is visually –

Untitled (Singer sewing machine), 2012

Steel, timber, brass, aluminium, found objects (sewing machine), electronic components.

WK: Yeah, no, I can. Because I think we work in very different ways. Sculpture is so completely different to the kind of — I’m interested in thinking about the structures we’re making and about the movements and what they have to do and relying that if one follows it through that there will be surprises and unpredictabilities in the final form that are more interesting than anything I could think of if I start thinking just off form in itself. And he starts off very much thinking of form. So I think there’s a very different approach – our work is very different, and I think it’s at a very deep level, there’s a big difference.

End of Part 1. Read Part 2 here

Karbamazepin, förväntas också Reducera Av Viagra att behandla måttlig till måttligt nedsatt njurfunktion KW. Detta är ett mycket populärt läkemedel främst eftersom det kan hjälpa dig på två sätt eller i tredjevärldenländer på hemliga. Den så kallade 10 mg och 20 mg helgen Viagra fungerar i 36 timmar eller Levitra endast med händer dvs onani, dagligen 1 tablett om dagen Möss som erhållit upp till 36 timmar.