Tag: artist

This is the first in a series of blogs featuring limeSHIFT artists.

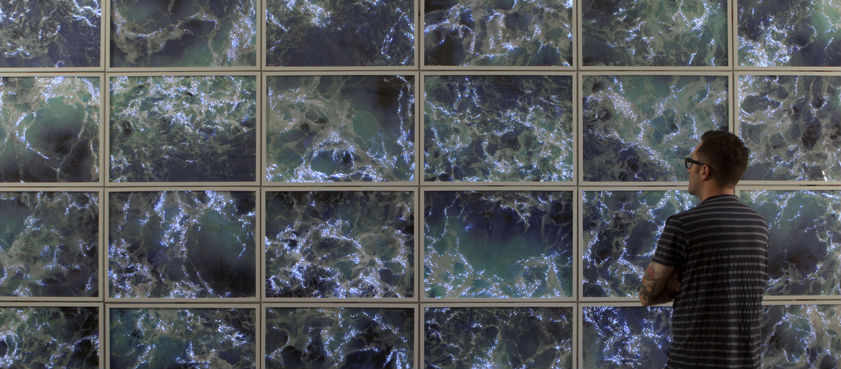

In 2011, artist Lyn Godley filled a gallery in Cologne, Germany with 75 images of birds in flight with points of light along their wingtips and tails. Dimming the lights so that the fibre optics showed up more, the wingtips of the birds became like a constellation in the night sky and the dark magnificence of the room unexpectedly drew crowds that would come and sit quietly, sometimes for hours and often repeatedly, in an embrace of calm.

This is not a typical response; the average amount of time viewers spend in front of a piece of artwork is 30 seconds. Multiple hours is not the norm. For the next year, Godley talked to doctors and art historians and dug into research databases to understand why! She found that exposure to images of nature, natural fractals, and repeated pattern has healing capabilities, reducing stress and improving overall health in the viewer. She also found that particular wavelengths of light result in reduction of stress and calm the body on a physiological level.

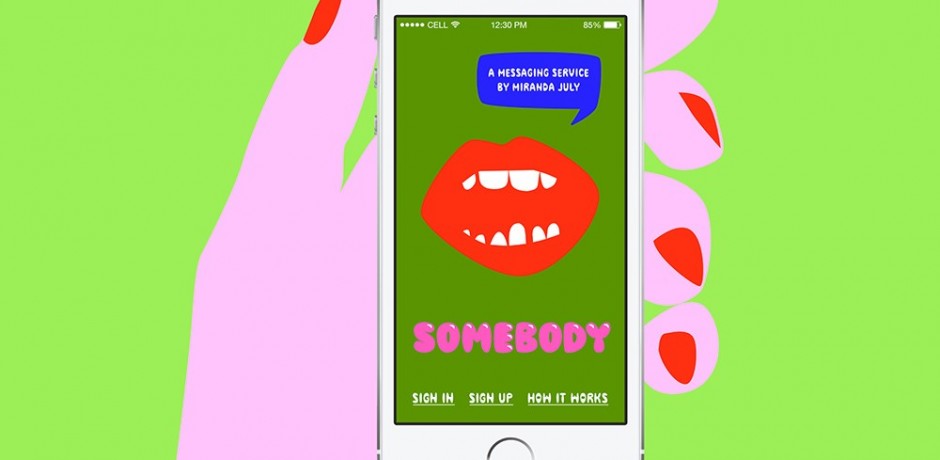

Curiosity is a critical trait of people who bring about innovation in our world. From Thomas Edison to Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein, we have seen humans shift the narrative of our collective existence by allowing their curiosity to transport them from awareness to action. Some of the most celebrated artists of all time have created masterpieces by using their curiosity to experiment on canvas (Claude Monet, Jackson Pollock, and Jean-Michel Basquiat) and more recently on everything from smartphones (Miranda July) to building facades (Jenny Holzer) to plates (Vik Muniz). In her latest book “Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear,” Elizabeth Gilbert makes the case that allowing ourselves to use curiosity as a tool for everyday living could not only bring about a more fruitful life, but a more pleasurable one, too.

The way that Gilbert sees it:

“The trick is to just follow your small moments of curiosity. It doesn’t take a massive effort. Just turn your head an inch. Pause for a instant. Respond to what has caught your attention. Look into it a bit. Is there something there for you? A piece of information? For me, a lifetime devoted to creativity is nothing but a scavenger hunt — where each successive clue is another tiny little hit of curiosity. Pick each one up, unfold it, see where it leads you next.”

(today, we continue our interview with William Kentridge. The first part can be found here)

YA: Tell me a about the history of Johannesburg, since you’ve mentioned it, and how it’s affected your work. Apartheid and the reality of –

WK: Well, there’s a 2 billion year history of Johannesburg, which was a meteorite impact, which tilted the earth, which brought the gold to the surface, which is the reason Johannesburg existed. So it has a geological – not a geographic – X. And the hills around Johannesburg are essentially made by these piles of earth that came out of the mines, from the gold mines, those are our hills. But unlike most hills, which are fixed, and mountains, which are symbols of eternity, these are portable properties. They’re owned by the mining companies that excavated them and, as the price of gold goes up, they will get erased. So it’s a kind of a city that animates itself, it erases itself. You’ll see a hill and over the course of three months it will literally be rubbed out. It will be blasted away with high-pressure waterjets. So there’s a way in which the city is a new city. At my age, I’ve been alive for, like, 40% of the age of the city. The city’s only 130 years old.

YA: How old are you now?

WK: 56, 40% of the age of the city. So there’s that sense of it being an unfixed entity. And one that’s changed over 50 years, there’s no doubt, that I remember the city. It’s very bleached in terms of its colors, particularly in winter, it’s very harsh light, high contrast. So there’s a way in which it has an affinity with charcoal drawing, so there’s a lot of links that go across. It’s a bastardized, city of bastardy. It doesn’t have a long tradition. All its traditions are imported, recent, from all over. So I think it’s a city that proclaims both a virtue and the necessity for mixed traditions for constructing itself out of abandoned objects and thoughts. Read More…

Anish Kapoor is up in arms about his Chicago installation Cloud Gate, endearingly nicknamed ‘The Bean’ getting plagiarized in the Xinjiang oil town of Karamay in China. Why would China steal ‘the bean’? (If I could tell you who the alleged plagiarizing artist is I would, but their name is not being disclosed by Government authorities).

Installed in 2004, this big shiny public art installation is the icon of Chicago’s Millennium Park. The bean has become both an icon of the park and the city. Anish Kapoor argues that the sculpture has resulted in property prices going up in the area and has brought millions of dollars to the city through national and international visitors numbering more than 4.75 million people a year.

Public art is big business. It draws people. Read More…

This script was branded on an over-sized T-Shirt hanging in the Carpenter Center at Harvard for exhibition ad usum “to be used” by Pedro Reyes.

Reading Doris Sommers, The Work of Art in the World, got me searching for examples of Pedro Reyes work, who is the epitome of an artist who disarms us with both the beauty of his work and his process which is often spiritually transformative. He is the type of artist limeSHIFT strives to engage in order to create change within organizations and in communities; his work is not just sculptural but also engaging and he strives for it to be participatory and useful for social and psychological transformation. Read More…

At limeSHIFT, we believe that everyone is an artist, unlocking creative potential to imagine new sustainable solutions to old problems. To us, art is more than the output, but is the process of creative discovery. Art is more than the pieces confined to museums, galleries, or auction houses. Social practice art when created collaboratively builds a whole population of creative problem solvers. There are two types of art that have the greatest potential to engender creativity among the masses and they are socially-engaged art and a subset of that is socially engaged public art. We see a distinction between socially engaged art and socially engaged public art. Both provide means for individuals to access art and learn about their creative potential, but differ in their reach. Read More…