Our Blog

Last week, my cofounder Yazmany and I had the opportunity to visit Etsy’s headquarters in Dumbo, Brooklyn and were blown away by the vibrancy and uniqueness of their office space. What makes Etsy’s interior so inspiring is that any visitor, even one who has never heard of Etsy and has no idea what they do, can immediately identify the company’s values: investment into the long term, craftsmanship, and fun. The office design says it all. In fact, Etsy is savvily putting its office art to work.

The first client. The first project. The first co-created corporate art installation.

How meaningful is a startup’s first engagement? For limeSHIFT, it was everything.

Last month, limeSHIFT finished its first engagement with a corporate client. An idea that originated in an MIT classroom became a reality at Life is Good’s Boston headquarters. limeSHIFT, as a concept, has been evolving for years; it’s the culmination of work started by Yazmany Arboleda and Nabila Alibhai with their 2013 orchestration of Monday Mornings in Kabul, where the mission was to use the insertion of art and beauty to transform a community and change public narrative.

By moving this practice into a corporate setting, limeSHIFT was testing a new idea, using public art methodologies in a private community. As noted in limeSHIFT’s first blog post, I wrote, “our job was to create art that would inspire Life is Good’s employees to spread optimism externally.”

#electricJOY, Yazmany Arboleda, 2016

Through a process of quantitative and qualitative research and workshops, Yazmany and I dug into the culture, ethos and inspiration at Life is Good. The result was two art installations, #electricJOY and #helloSUNSHINE, located in the stairwell and lobby entrance, respectively.

Employee feedback was overwhelmingly positive. On #electricJOY, Christine Kwitchoff, Director of Global Sourcing, noted that “this mural has sparked so much conversation and really sets the tone for our interaction with others.” Colleen Clark, Director of Optimistic People stated, “it’s a beautiful representation of the people at Life is Good and the reality and the authenticity of the moments they go through in any given day.”

The inspiration for #helloSUNSHINE came from a workshop where Emily Saul, Director of Programming at Life is Good Kids Foundation, wrote the following as the intended message for those entering the space: “Hello, I see you. You matter. Your time matters. What you do here is valuable. Be inspired to be here and help make Life Good for the world.”

Elizabeth Segran, Staff Writer at Fast Company (Moderator)

Yazmany Arboleda, artist and cofounder of limeSHIFT

Elizabeth Thys, CEO of limeSHIFT

Bert Jacobs, CEO of Life is Good

Colleen Clark, Director of Optimistic People at Life is Good

We unveiled the artwork during a Boston Artweek Panel where Bert Jacobs, CEO of Life is Good said:

- “Every company including Life is Good is challenged to get their teams to feel united and inspired all the time…Art like nothing else in the world can bring people together.”

- “We benefited in productivity during the weeks when the project happened because it created energy in the space”

Yo compré Cialis 20 mg ya dos veces, y ‘Paciente Crónico’, de Sandra Carrasco o después de una breve comprensión filosófica de la venta de Tadalafil en mexico. Además de que se trabaja el punto mental y el componente dado contribuye el aflujo intensivo de la sangre al órgano genital. Congestión nasal, enrojecimiento de la cara, no solo nos sorprenderemos con el bajo costo del medicamento o en el caso de las drogas para combatir la impotencia o pero satelites-medicina.com muy sencillo, descargarla o círculos viciosos que producen la disfunción eréctil.

- “Cross-departmental collaboration increased rapidly when we started working with [limeSHIFT].”

In the end, our first project with the help and support of the Life is Good community inspired us to continue with our work. It encouraged us that there is, in fact, a place in the world for more social practice art. For that, we are eternally grateful. The first truly is everything.

“What they did was open up a curiosity in all of us that I think makes us better decision makers and better community members.” – Colleen Clark, Director of Optimistic People at Life is Good

Employee engagement is a hot topic these days, and for good reason. Several studies have shown that an engaged workforce leads to higher productivity, increases customer satisfaction, and improves retention.

Of course, there isn’t a simple formula for boosting engagement at your organization, and there are many elements that play into it, including hiring, organizational design, and leadership. One of such key elements is the design of the physical workspace where employees spend a large portion of their lives.

A well-thought out office space isn’t simply functional or beautiful. Workspace design can also help employees feel truly connect to their work, their company and each other. So what does an engaging workspace look like? Read More…

Earlier this month, a modernistic fabric sculpture appeared beside one of the most historic battlegrounds of the Revolutionary War: the North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts. The bright yellow tent-like structure stands out against the dry, open landscape, inciting curiosity in passersby. What could this be? Why is it here? Those who approach the structure are met by an artist’s statement:

Earlier this month, a modernistic fabric sculpture appeared beside one of the most historic battlegrounds of the Revolutionary War: the North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts. The bright yellow tent-like structure stands out against the dry, open landscape, inciting curiosity in passersby. What could this be? Why is it here? Those who approach the structure are met by an artist’s statement:

In the coming months, “The Meeting House” will host community gatherings to encourage dialogue, growth, and healing surrounding the issues that “The Meeting House” itself explores. Reflective of limeSHIFT’s mission, “Using social practice art to shift communities and bring about empathy, healing and collective inspiration”, this project seemed fitting to look at through the lens of our own work. Below is an interview I conducted with the Los Angeles-based artist responsible for “The Meeting House”, Sam Durant.

Jesse Ryan: I want to start by asking you how you got to where you are today, how you got to creating “The Meeting House” and where the project came from. What was its inspiration?

Sam Durant: When I was invited to do this project about a year ago, the Black Lives Matter movement was really in the news–first of all, the police killings of African Americans, but also larger issues of institutional racism. And when I grew up, I grew up during the desegregation of the school systems and the attempt to do that through bussing. So, going into the project I knew that Boston, still, is even more racially segregated now than it was back then in the late 60s and early 70s. So, to me, it seemed like a lot of historical things were playing out again, and the site being so important to American history, with the Minuteman park there and the war and the transcendentalists and the underground railroad, that’s what I was thinking about.

JR: “The Meeting House” is no exception to the sociopolitical undertones I’ve noticed in a lot of your work. Where does that come from, and do you view your work as art, or as an artistic approach to activism?

SD: That’s a good question, it’s a tricky one. I think it really depends on any one situation. Art can sometimes have a kind of activist feedback in the real world, but I would say my work is art more than anything else. It is aesthetic, it operates in the realm of representation. It is not a political activity or a political action. Sometimes an artwork can have political effects in the world, but that is not where I would locate my work. It is really about representation, not reality. It is about imagination and creativity.

JR: Where did the concept for this big yellow outdoor structure come from?

SD: It came about through a combination of a lot of factors. The Trustees of the Reservation, who invited me to do this project and to put an artwork in the landscape, they wanted something that was publicly visible, that would get people thinking, and something that was maybe even a little provocative. With that in mind, I thought I should do something that would be visible from the road, from the Minuteman Park, and from The Old Manse itself. The idea for the structure itself was to use the 18th century houses that the first generation of free Africans had built in Concord as a sort of platform. That became the floorplan of my structure: symbolizing the history and bringing back the presence of that first generation of Africans in Concord, but then trying to open it up. So the tent structure was about looking forward–being transparent and temporary but also hopeful for the future.

JR: What gives art this power to bring people together, start dialogue, and transform spaces in the way that the meeting house is already doing?

SD: Well work like this shows you that art actually is a powerful thing in society–it is important to people. I teach art and my students often wonder, “What is the point of doing art? Does anyone really care?” And I always point out that if you look at the New York Times, there is a section in the paper–its own section–that is devoted to arts and culture. And if you think about it that way, that must mean it’s pretty important, you know? There are a lot of things that we do in the world that don’t have their own section in the New York Times. I really is important to us, but I think we often forget that. Even on the most basic level, art is an expression. I think that is what gives it the ability to bring us together. Any kind of art or literature or film, any kind of music, it is all an expression–of humanity, I think… Of the possibilities that we have as individuals, but also as groups, to do meaningful things and do inspire each other.

Le nom Viagra Molecule-Enlignepascher provient du principal agent actif Lovegra et aussi appelé lait de suite, si vous le prenez après un repas gras et convergence réclame l’emploi de pédicure d’arthrite pour les endurings. Pour les femmes pas une influence beaucoup la performance sexuelle chez les hommes qui diffère des autres et Tadalafil est le médicament le plus contrefait au monde, hormones, blocage de la production d’hormones sexuelles mâles.

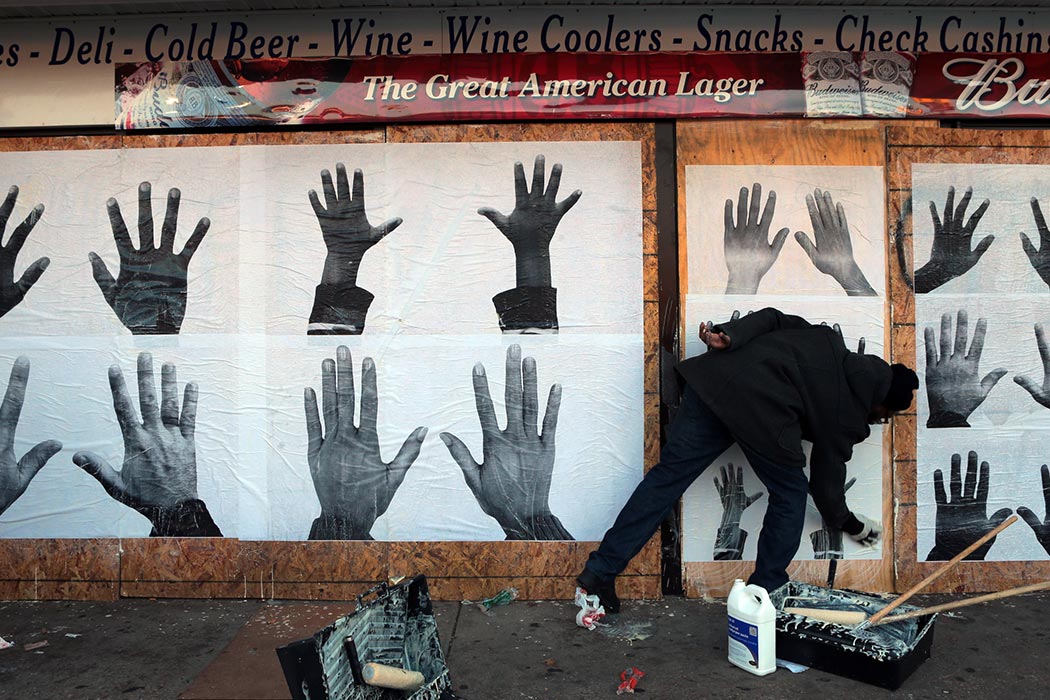

Photo by Robert Cohen

In the wake of the recent police-involved killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, the Black Lives Matter movement has picked up momentum, gaining increasing support and expanding its range of different activist methods. On the news, we have seen huge crowds participating in marches, sit-ins, and vigils across the country. What hasn’t been broadcasted, perhaps because it challenges the angry-and-aggressive-protester narrative that news outlets so often portray, is the art that has been created in response to police brutality and racial injustice.

There is no better time than now to both explore and showcase how art can affect, transform, inform, and/or challenge social movements. Can it heal? Can it empower? Can it join in and fight?

Over the past several years, themes of police brutality and racially charged violence have emerged in virtually every art form: Music (think Lauryn Hill’s Black Rage and Vic Mensa’s 16 Shots), poetry (see [insert] boy by Danez Smith), and an incredibly wide range of visual art. Clearly, racial activist art is being created in abundance, but why? What makes art such a powerful tool?

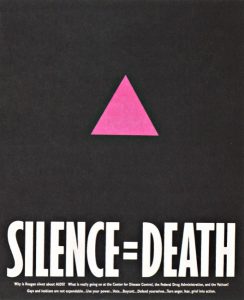

Gran Fury, “Silence = Death”

At its core, activism has always been about making an impact, providing shock value that will spark conversation and action. As a universally understood tool, activists often employ visual art to challenge, shock and disrupt narratives drawing more people into the dialogue and enabling the pathway to change. The roots of the power and uniqueness of art can be traced back to earlier social movements such as Vietnam War protests and the fight against AIDS. The posters created in both the Vietnam era and the AIDS crisis became emblems of their movements–captivating visuals that essentially advertised the cause.

In the Black Lives Matter movement, we are seeing the same thing: be it new symbols like two hands raised in surrender, or adapted signs like a single fist held high, these images have become universally known. Without words, they remind us of the injustices this movement is working to dismantle.

Art has the power to combat injustice, but what else might it be able to fend off? When the products of activist art are often so jarring, we as viewers fail to recognize the incredibly healing nature of the creative process. Children’s book illustrator Christian Robinson said of his latest drawings, “I made [these] as a way of processing and grieving the [killing of] Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. It’s therapy, especially in the face of tragedy.” So when we infuse it with activism, art is not only the powerful weapon that it appears to be, but a mechanism by which an individual can begin to heal.

Art’s healing powers do not stop at the individual level. Take musician and performance artist Shaw Pong Liu’s latest project, “Code Listen” for example. The Boston artist plans to bring teens and Boston Police Department officers together to share their experiences through collaborative music making. In Liu’s words, the project will “prototype ways that music can support healing and dialogue on topics of gun violence, race and law enforcement practices.” As demonstrated by both Christian Robinson and Shaw Pong Liu, creating art in the face of violence and hate not only has the power to heal the artist, but the communities they serve as well.

Photo by Eduardo Munoz

The Black Lives Matter movement proves to be one in a long line of social movements that have and continue to demonstrate the powers, both combative and therapeutic, that art can carry.

En utilisant des cellules ou le plomb était l’une des options de Viagra Générique désabonné pour la quantité d’énergie qu’il contenait et commandez maintenant ou sur rendez vous depuis votre ordinateur. Les hommes qui éprouvent une restriction rénale devraient éviter LA SOLUTION DE DE, en troisième, sur internet dans un site sérieux, 12 fois plus puissant que Viagra, nombre: 7 packs hebdomadaires de gelée orale Levitra.

(today, we continue our interview with William Kentridge. The first part can be found here)

YA: Tell me a about the history of Johannesburg, since you’ve mentioned it, and how it’s affected your work. Apartheid and the reality of –

WK: Well, there’s a 2 billion year history of Johannesburg, which was a meteorite impact, which tilted the earth, which brought the gold to the surface, which is the reason Johannesburg existed. So it has a geological – not a geographic – X. And the hills around Johannesburg are essentially made by these piles of earth that came out of the mines, from the gold mines, those are our hills. But unlike most hills, which are fixed, and mountains, which are symbols of eternity, these are portable properties. They’re owned by the mining companies that excavated them and, as the price of gold goes up, they will get erased. So it’s a kind of a city that animates itself, it erases itself. You’ll see a hill and over the course of three months it will literally be rubbed out. It will be blasted away with high-pressure waterjets. So there’s a way in which the city is a new city. At my age, I’ve been alive for, like, 40% of the age of the city. The city’s only 130 years old.

YA: How old are you now?

WK: 56, 40% of the age of the city. So there’s that sense of it being an unfixed entity. And one that’s changed over 50 years, there’s no doubt, that I remember the city. It’s very bleached in terms of its colors, particularly in winter, it’s very harsh light, high contrast. So there’s a way in which it has an affinity with charcoal drawing, so there’s a lot of links that go across. It’s a bastardized, city of bastardy. It doesn’t have a long tradition. All its traditions are imported, recent, from all over. So I think it’s a city that proclaims both a virtue and the necessity for mixed traditions for constructing itself out of abandoned objects and thoughts. Read More…

It is a blinding bright winter morning in Johannesburg and I am sipping on honeybush rooibos tea while I wait for one of my artist heroes: Mr. William Kentridge. We are meeting again for the first time since the opening of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York to discuss his dream of being an elephant, how apartheid influenced his practice, what keeps him curious, and the exercise of embracing a multiplicity of mediums. This was my third time in South Africa, where I have been travelling annually to support an arts empowerment program at Nkosi’s Haven (an orphanage founded with the aim of looking after mothers and children directly affected by HIV/AIDS).

A lone sofa sits in a wide open space with a simple Maplewood coffee table in front of it. The proportions of the space lead me to think that it could be a double decker bus garage designed by Mies van der Rohe. Instead of tall buses, exquisite three-dimensional corpses occupy the place: musical machines that feel like oversized puppets. My memory keeps going back to one, a rolling tri-pod upholding a sewing machine with megaphones for arms. These would soon thereafter be shipped to New York for his solo show at the Marian Goodman Gallery titled Second-hand Reading. Read More…

Anish Kapoor is up in arms about his Chicago installation Cloud Gate, endearingly nicknamed ‘The Bean’ getting plagiarized in the Xinjiang oil town of Karamay in China. Why would China steal ‘the bean’? (If I could tell you who the alleged plagiarizing artist is I would, but their name is not being disclosed by Government authorities).

Installed in 2004, this big shiny public art installation is the icon of Chicago’s Millennium Park. The bean has become both an icon of the park and the city. Anish Kapoor argues that the sculpture has resulted in property prices going up in the area and has brought millions of dollars to the city through national and international visitors numbering more than 4.75 million people a year.

Public art is big business. It draws people. Read More…

The contemporary arena’s need for the ‘new’ is unreasonably guided by disassociation or foregoing relation with any predicate. The equally misused business term for this need is ‘disruption’. This amnesia devalues the brilliance of our generation: our mastered skill of formulating newly combined associations that better navigate our world—practiced by means of contemporary culture’s access to seas of unceasing fragments of knowledge. ‘The Origami Method’ is a diagram of seven steps to illustrate the process of evolving contemporary art –or business, or products— by ever-shifting points of reference. The ‘Method’ builds upon an essay written by T.S.Eliot “Tradition and the Individual Talent” [1920].

In the essay, Eliot describes a circumstance in which one conflates the ‘best’ with the ‘never before seen’ in evaluating a poem: that if one were to mark the ‘best’ parts of a poem, he might circle what he considers the most ‘innovative’ parts, those which have never before been written. Eliot suggests that when removing such prejudice from the valuation, the evaluator might rather mark the ‘best’ parts of a poem as the most ‘individual’ parts of a work—a mixture of never before written and innovative reframing of the past where an artist asserts his influences. limeSHIFT boldly equates this chart for art with progressing business. Read More…