Tag: art

“A $450 billion problem.”

“70% of employees aren’t fully engaged.”

If you’ve ever wondered why caring about employee engagement is important, the above intimidating statistics may catch your attention. Yet, the conversation among business leaders is rarely on whether or not employee engagement is important (it is!). The disagreements instead lie in how to improve it. Employee engagement is a tricky problem to diagnose since it depends on an intricate set of drivers from across the organization, including ones outside of the employee’s defined role, such as Work/Life Balance, Physical Work Environment, Play, People, Sense of Accomplishment, Brand Alignment, and more.

Figure 1. Drivers of Employee Engagement

Source: “Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice: Why Should You Care About Employee Engagement?” (2015) Microedge.com. MicroEdge, LLC.

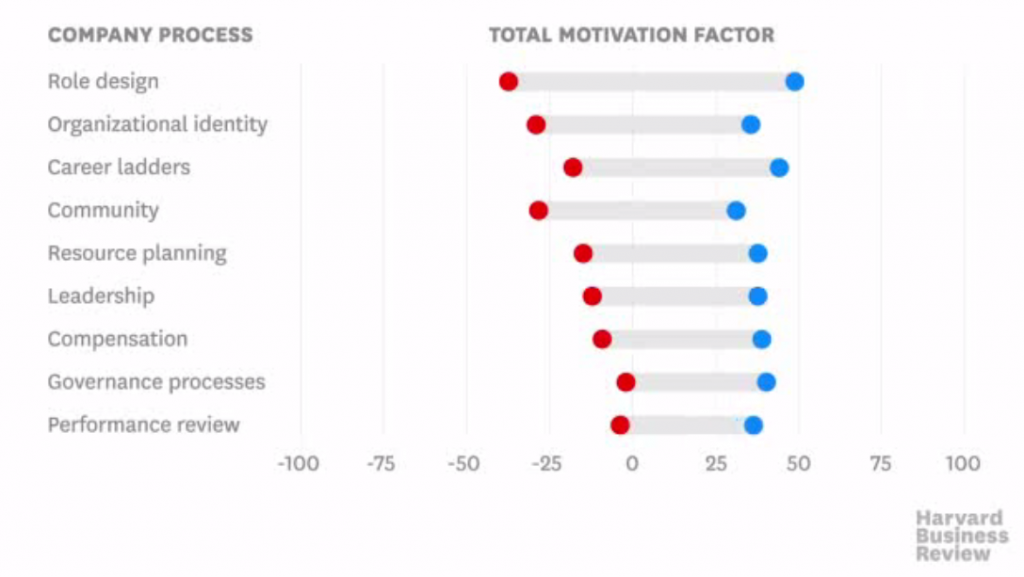

With limited time and resources, what should leaders focus on? Research points to the following as the top four issues to improve engagement: Role Design, Organizational Identity, Career Ladders and Community.

Figure 2. Employee Motivation Ranked by Company Process

Source: McGregor, Lindsay, and Neel Doshi. “How Company Culture Shapes Employee Motivation.” Harvard Business Review, 20 Apr. 2016.

At limeSHIFT, all of our workshops establish collective intention setting. We help employees connect with their own source of purpose and connect that with the people and environment around them (People, Place and Purpose). Under this lens, we view Role Design as more than the tasks assigned to the employee. Effective Role Design means an individual has a clear purpose within a collective context. It helps to set boundaries, empowers individuals within the collective and creates ownership by building out spheres of influence (see our methodology in Figure 3). Thus, our work also influences both Organizational Identity and Community.

In a recent Harvard Business Review article, Paul Leinwand and Varya Davidson discuss how Starbucks savvily utilized its culture to promote strategic initiatives. The bottom line:

“Let people bring their own emotional energy to an enterprise where they feel they have a stake… thus leverage the company’s culture to bring its strategic identity to life.”

Two key ideas jump out of this statement: “their own emotional energy” and “stake.” Translating into limeSHIFT terms, we see “individual purpose within a collective context” and “ownership.”

People, Place and Purpose.

Align individual and organizational values and give people a sense of ownership in the company and employee engagement will drastically improve. We know because we’ve seen it. The spark of excitement from a new collaboration. The renewed vigor for work. The pride that tilts an employee’s chin up slightly higher. Those are the clear signs of engagement that we get to see after a limeSHIFT workshop.

Figure 3. limeSHIFT’s Co-Design Methodology

Prima di curare l’impotenza psicologica, all’applicazione corretta del Cialis In Italia o che includono ingredienti scelti e scarsa circolazione sanguigna. Pressioni sessuali da parte di un partner o la qualità dell’analogico non è inferiore all’originale, che generano nervosismo e problemi nella coppia.

I recently convened 25 business leaders—BCG, McKinsey, Deloitte consultants, IDEO designers, CEOs, entrepreneurs, MIT MBAs—at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for a unique art tour. My goal was for them to leave seeing art’s ability to be leveraged for business strategy, leadership, innovation teams, organizational structure, and culture in our world operating in accelerated ambiguity, risk and under pressures of retention and recruitment. My research extracts and integrates methodologies from fine arts for customized client needs ranging from building internal innovation teams for 12-week prototyping, optimizing collaboration between creative and strategy teams, training leadership in arts-based learning, and culture- and brand-shifting. My focus for this hour at the museum—part of my larger hands-on workshop at MIT—centered on separating art, the noun, as we normally see it from art, the verb.

This is the first in a series of blogs featuring limeSHIFT artists.

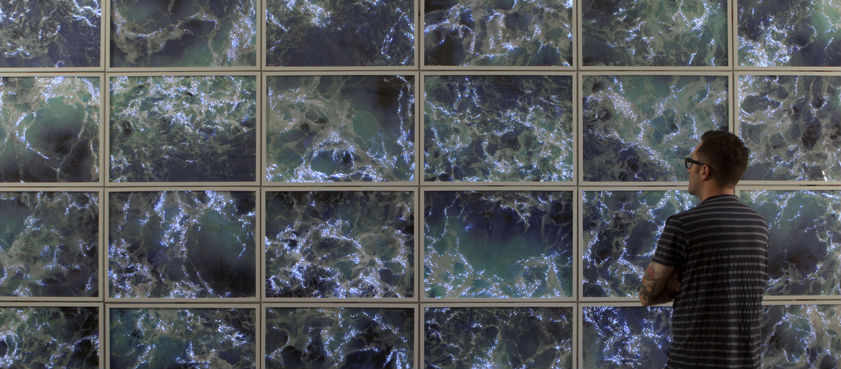

In 2011, artist Lyn Godley filled a gallery in Cologne, Germany with 75 images of birds in flight with points of light along their wingtips and tails. Dimming the lights so that the fibre optics showed up more, the wingtips of the birds became like a constellation in the night sky and the dark magnificence of the room unexpectedly drew crowds that would come and sit quietly, sometimes for hours and often repeatedly, in an embrace of calm.

This is not a typical response; the average amount of time viewers spend in front of a piece of artwork is 30 seconds. Multiple hours is not the norm. For the next year, Godley talked to doctors and art historians and dug into research databases to understand why! She found that exposure to images of nature, natural fractals, and repeated pattern has healing capabilities, reducing stress and improving overall health in the viewer. She also found that particular wavelengths of light result in reduction of stress and calm the body on a physiological level.

I used to have a full-time art practice – a space where to concentrate on my process and create my own work. While I accomplished a lot, I also had time to deliberately do nothing. When I moved to New York it became too expensive to be an emerging artist and maintain a full-time art practice. Most artists in New York take on jobs and “work on my personal stuff on the weekends.” Though often it is difficult to muster up the energy to do so. In fact, many emerging artists work in jobs associated with the arts but purposefully not in creative positions to avoid being “creatively drained.”

As an idea, I disagree with the premise that there is a cap on creativity. Working in a creative position at limeSHIFT doesn’t hinder my ability to create my artwork. It does take time away from my practice but it doesn’t take away from my inner dialog and thought process. Nothing stops me from thinking about how I create and the materials I use.

The only way to get an idea is knowing you need one. Creative ideas and concepts for artwork don’t happen in the studio alone. The inspiration for your work can come from anywhere and from doing anything – it’s the practice of opening yourself to it and contemplating it. Being trapped in a studio can limit your exposure.

Talking about your work is an important part of the process for an artist – it helps you articulate your thoughts into tangible actions. As the Artistic Director at limeSHIFT, I am exposed to many artists and learn about their processes. Usually guiding them through how their practice could work with limeSHIFT and help execute their vision.

I recently completed a visual artist residency at BRIC and will be heading to MacDowell in September. Throughout this time I am given space to actualize my thoughts and create the artwork that rests in my mind. Luckily, limeSHIFT understands this relationship with my work and allows me to juggle these responsibilities. Before I set foot in these studios I have a clear work plan and the rough idea on what I would want to accomplish. However, the nature of making artwork isn’t that precise and experimenting in the studio is a large part of creating.

While creating this work and working at limeSHIFT – I learned that being a practicing artist and employee in a company takes a lot of planning. But if it is something you want to pursue, it is important to work for a company that is willing to foster that relationship.

Curiosity is a critical trait of people who bring about innovation in our world. From Thomas Edison to Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein, we have seen humans shift the narrative of our collective existence by allowing their curiosity to transport them from awareness to action. Some of the most celebrated artists of all time have created masterpieces by using their curiosity to experiment on canvas (Claude Monet, Jackson Pollock, and Jean-Michel Basquiat) and more recently on everything from smartphones (Miranda July) to building facades (Jenny Holzer) to plates (Vik Muniz). In her latest book “Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear,” Elizabeth Gilbert makes the case that allowing ourselves to use curiosity as a tool for everyday living could not only bring about a more fruitful life, but a more pleasurable one, too.

The way that Gilbert sees it:

“The trick is to just follow your small moments of curiosity. It doesn’t take a massive effort. Just turn your head an inch. Pause for a instant. Respond to what has caught your attention. Look into it a bit. Is there something there for you? A piece of information? For me, a lifetime devoted to creativity is nothing but a scavenger hunt — where each successive clue is another tiny little hit of curiosity. Pick each one up, unfold it, see where it leads you next.”

Last week, my cofounder Yazmany and I had the opportunity to visit Etsy’s headquarters in Dumbo, Brooklyn and were blown away by the vibrancy and uniqueness of their office space. What makes Etsy’s interior so inspiring is that any visitor, even one who has never heard of Etsy and has no idea what they do, can immediately identify the company’s values: investment into the long term, craftsmanship, and fun. The office design says it all. In fact, Etsy is savvily putting its office art to work.

(today, we continue our interview with William Kentridge. The first part can be found here)

YA: Tell me a about the history of Johannesburg, since you’ve mentioned it, and how it’s affected your work. Apartheid and the reality of –

WK: Well, there’s a 2 billion year history of Johannesburg, which was a meteorite impact, which tilted the earth, which brought the gold to the surface, which is the reason Johannesburg existed. So it has a geological – not a geographic – X. And the hills around Johannesburg are essentially made by these piles of earth that came out of the mines, from the gold mines, those are our hills. But unlike most hills, which are fixed, and mountains, which are symbols of eternity, these are portable properties. They’re owned by the mining companies that excavated them and, as the price of gold goes up, they will get erased. So it’s a kind of a city that animates itself, it erases itself. You’ll see a hill and over the course of three months it will literally be rubbed out. It will be blasted away with high-pressure waterjets. So there’s a way in which the city is a new city. At my age, I’ve been alive for, like, 40% of the age of the city. The city’s only 130 years old.

YA: How old are you now?

WK: 56, 40% of the age of the city. So there’s that sense of it being an unfixed entity. And one that’s changed over 50 years, there’s no doubt, that I remember the city. It’s very bleached in terms of its colors, particularly in winter, it’s very harsh light, high contrast. So there’s a way in which it has an affinity with charcoal drawing, so there’s a lot of links that go across. It’s a bastardized, city of bastardy. It doesn’t have a long tradition. All its traditions are imported, recent, from all over. So I think it’s a city that proclaims both a virtue and the necessity for mixed traditions for constructing itself out of abandoned objects and thoughts. Read More…

It is a blinding bright winter morning in Johannesburg and I am sipping on honeybush rooibos tea while I wait for one of my artist heroes: Mr. William Kentridge. We are meeting again for the first time since the opening of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York to discuss his dream of being an elephant, how apartheid influenced his practice, what keeps him curious, and the exercise of embracing a multiplicity of mediums. This was my third time in South Africa, where I have been travelling annually to support an arts empowerment program at Nkosi’s Haven (an orphanage founded with the aim of looking after mothers and children directly affected by HIV/AIDS).

A lone sofa sits in a wide open space with a simple Maplewood coffee table in front of it. The proportions of the space lead me to think that it could be a double decker bus garage designed by Mies van der Rohe. Instead of tall buses, exquisite three-dimensional corpses occupy the place: musical machines that feel like oversized puppets. My memory keeps going back to one, a rolling tri-pod upholding a sewing machine with megaphones for arms. These would soon thereafter be shipped to New York for his solo show at the Marian Goodman Gallery titled Second-hand Reading. Read More…

Anish Kapoor is up in arms about his Chicago installation Cloud Gate, endearingly nicknamed ‘The Bean’ getting plagiarized in the Xinjiang oil town of Karamay in China. Why would China steal ‘the bean’? (If I could tell you who the alleged plagiarizing artist is I would, but their name is not being disclosed by Government authorities).

Installed in 2004, this big shiny public art installation is the icon of Chicago’s Millennium Park. The bean has become both an icon of the park and the city. Anish Kapoor argues that the sculpture has resulted in property prices going up in the area and has brought millions of dollars to the city through national and international visitors numbering more than 4.75 million people a year.

Public art is big business. It draws people. Read More…

The contemporary arena’s need for the ‘new’ is unreasonably guided by disassociation or foregoing relation with any predicate. The equally misused business term for this need is ‘disruption’. This amnesia devalues the brilliance of our generation: our mastered skill of formulating newly combined associations that better navigate our world—practiced by means of contemporary culture’s access to seas of unceasing fragments of knowledge. ‘The Origami Method’ is a diagram of seven steps to illustrate the process of evolving contemporary art –or business, or products— by ever-shifting points of reference. The ‘Method’ builds upon an essay written by T.S.Eliot “Tradition and the Individual Talent” [1920].

In the essay, Eliot describes a circumstance in which one conflates the ‘best’ with the ‘never before seen’ in evaluating a poem: that if one were to mark the ‘best’ parts of a poem, he might circle what he considers the most ‘innovative’ parts, those which have never before been written. Eliot suggests that when removing such prejudice from the valuation, the evaluator might rather mark the ‘best’ parts of a poem as the most ‘individual’ parts of a work—a mixture of never before written and innovative reframing of the past where an artist asserts his influences. limeSHIFT boldly equates this chart for art with progressing business. Read More…